The 2024 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Automotive Trends Report

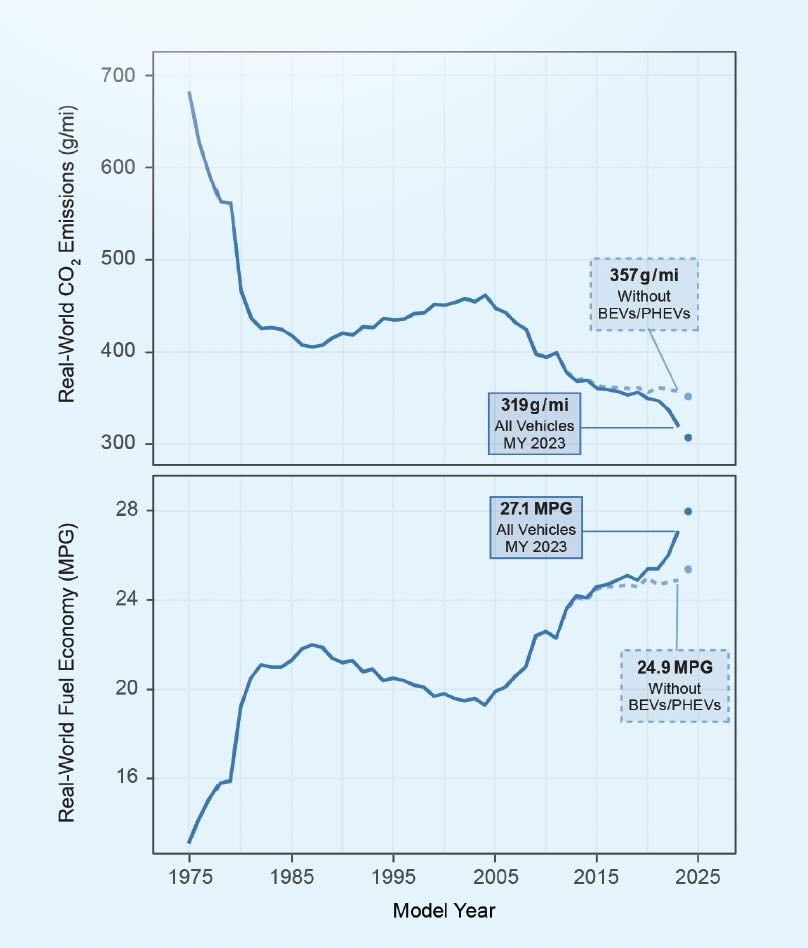

1 is available, and as usual, it is a treasure trove of data on the recent evolution of the automobile industry. Data on every new light-duty vehicle model sold in the U.S. is collected and summarized over 187 pages, 67 figures and 36 tables. The report is also a handy scorecard on the achievements of the automotive tribologist over the past half-century. One example is presented in Figure 1, which shows the progress on fuel economy and CO

2 emissions.

Figure 1. Progress on fuel economy and CO2 emissions.1

Figure 1. Progress on fuel economy and CO2 emissions.1

Both curves illustrate the same trends, namely rapid improvement in fuel economy and emissions from 1975 to 1987, gradual declines from 1987 through 2004, then another rapid increase through 2015, when both curves are split. After 2015, there is only modest improvement when considering petroleum-fueled vehicles, while the improvements continue at a significant pace when adding in the contributions from battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs).

So, why has the curve for the internal combustion engine (ICE) plateaued? Have engine manufacturers stopped investing in improvements? Chapter 4 of the report makes clear this is not the case. Engine technology has continued to evolve, but the gains are reflected in increased power output of an engine, rather than toward improving fuel economy.

The biggest challenge to improving efficiency may just be the amount of progress that has been made to date. Thermodynamics puts an absolute limit on how efficient any heat engine (i.e., a device that converts heat into useful work) can be. The so-called Carnot limit for a gasoline engine is around 60%. A review of modern production engines

2 suggests commercial engines are now operating at around 40% efficiency, which seems to suggest further progress is possible, even likely.

However, from a practical standpoint, some power will always be lost to friction. Also, some of the power must be put to other uses besides propelling the vehicle, such as running accessories and pumping various fluids (fuel, coolant, etc.). The net result may be that we have reached a point of diminishing return, where the cost and complexity of achieving the next level of efficiency is no longer something the consumer is willing to bear.

The most likely path to improved efficiency, therefore, is increased vehicle electrification. Demand for electric vehicles (EVs) and PHEVs continues to rise. From 2014 to 2024, the production share of these electrified vehicles has risen from about 1% to nearly 15%. Whether this trend continues in the U.S. remains to be seen. EV prices continue to drop to the point where they are approaching parity with similar ICE vehicles, range between charges continues to increase (basically doubling between 2014 and 2024), and charging infrastructure continues to grow. On the other hand, charging time remains an issue for most drivers, while subsidies and tax incentives for EV purchases are likely to be phased out. The results of these competing pressures remain to be seen.

REFERENCES

1.

EPA-420-R-24-022 (November 2024),

The 2024 EPA Automotive Trends Report: Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Fuel Economy, and Technology since 1975. Available at

www.epa.gov/automotive-trends.

2.

Dahham, R.Y., Wei, H. and Pan, J. (2022), “Improving thermal efficiency of internal combustion engines: Recent progress and remaining challenges,”

Energies, 15 (17), 6222,

https://doi.org/10.3390/en15176222.