TLT: How did you get started in the lubrication and oil analysis field?

Barnes: Back in the mid-1990s, I was looking to get out of a research position in academia and really didn’t have a clue what I wanted to do, other than to do something where my academic training could be used “in the real world.” One day, completely out of the blue, I happened upon a posting for a field sales engineering role with a commercial oil analysis lab, and it seemed to be a perfect fit—a great blend between my analytical chemistry background and my interest in “big machines” born from many high school summers spent onboard tugboats, where my father worked his whole life.

I still remember my first day “on the job” working in the lab to learn the business of oil analysis and performing 700 crackle tests! I honestly went to graduate school for four years to earn my doctorate degree to learn how to throw oil onto a hot plate!

This year marks my 28th year in lubrication and oil analysis, and I’ve been a passionate consultant, educator and mentor to countless companies and individuals in North America and around the globe.

TLT: What do you like most about your role?

Barnes: Variation! One day I can be in a classroom teaching a group of reliability engineers about oil analysis and precision lubrication, the next crawling around a steel mill or papermill looking at different applications and providing advice and recommendations for improving asset reliability through precision lubrication. I really enjoy helping people that have little to no background in lubrication or oil analysis learn and apply new skills to the benefit of both their employer and their own personal development.

I remember one career oiler (lubrication technician) who came into class with little knowledge about lubrication, who by the end of the third day, asked my opinion on the grease they were using on the press rolling bearings on their paper machine and whether I thought a Kappa value of 2.4 was appropriate, based on the calculations he had done the previous evening. Seeing someone “get it” is the most gratifying thing I do each and every day.

TLT: What are the biggest challenges people involved in lubrication are facing today?

Barnes: Like any technical field, oil analysis and lubrication are constantly evolving. However, at the core, precision lubrication has always been about ensuring that lubricant is clean, dry and in good condition, so in that sense, things really aren’t that different. Like any process that has a human component, most challenges come not from technology but from the culture and how organizations perceive the critical role that lubrication plays in asset reliability.

Like every industry, the retirement of the baby boomer generation has left a gap in the work force in the maintenance and reliability field. While some technologies like vibration analysis appeal to the “gamer” generation, lubrication is not so glamorous—finding people who have the skills, aptitude and most importantly the desire to succeed in a lubrication role is often what most companies struggle with. Training is a key component to cultural success, which is why I’m proud to have been teaching lubrication and oil analysis for nearly 30 years.

TLT: For anyone seeking to improve their company’s lubrication practices, what’s the best thing they can do?

Barnes: When I first started in this industry, lubricants were very much considered a consumable—to be purchased at the lowest costs and changed or reapplied frequently in a misguided attempt to try to ensure asset reliability. In the past five to 10 years with the evolution of ISO 55000 and other related asset management standards, those organizations that have the best lubrication practices treat their lubricants as assets that need to be nurtured.

Specific to the field of lubrication, the International Council for Machinery Lubrication (ICML) has developed a series of standards under the ICML 55 banner to provide an overview of the key elements of a precision lubrication program, along with prescriptive guides to help companies develop a plan.

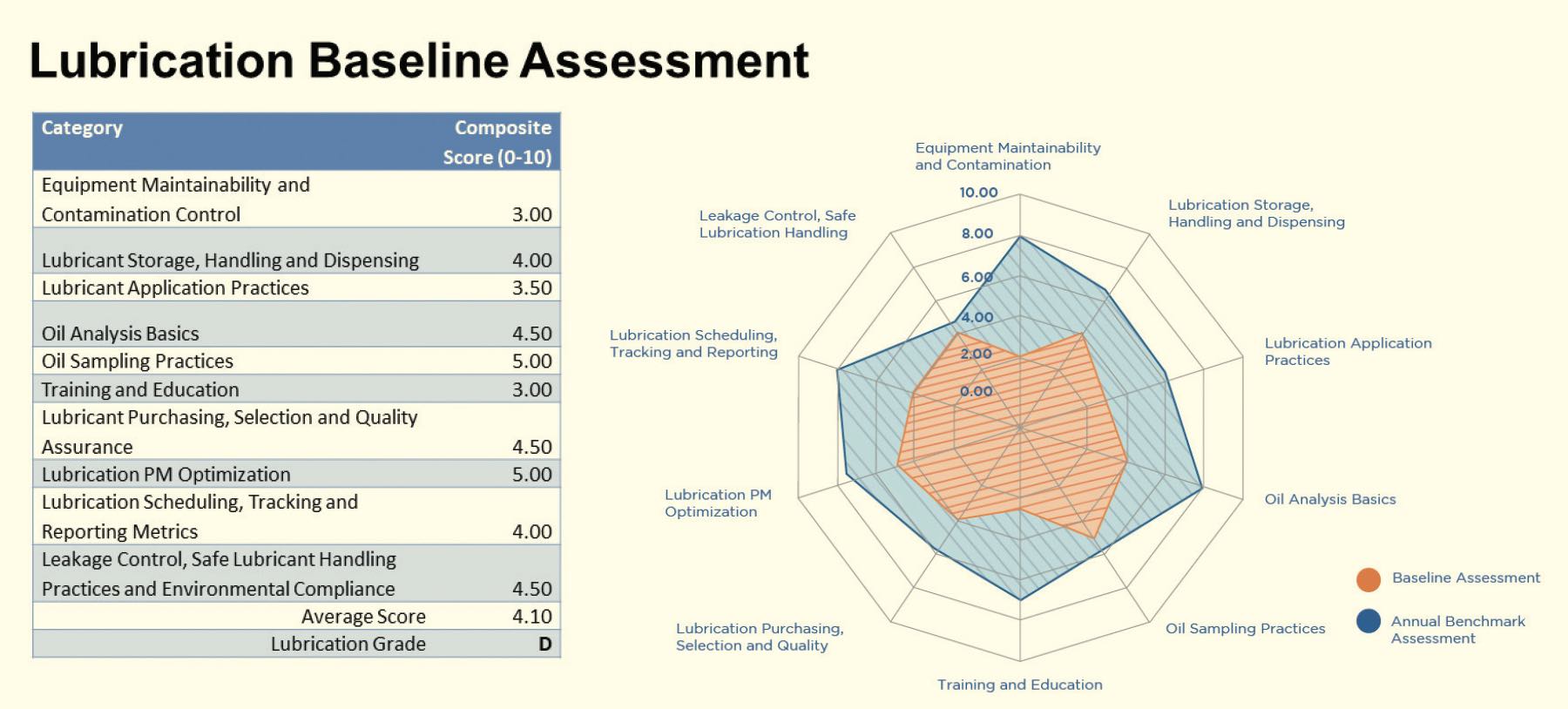

For any organization intent on changing their approach to lubrication, probably the best place to start is to bring someone in who has helped other companies achieve good lubrication practices and have them audit your practices compared to best in class

(see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A lubrication baseline assessment is usually a good way of developing an action plan as well as evaluating performance on an annual basis. Figure courtesy of Des-Case Corp.

Figure 1. A lubrication baseline assessment is usually a good way of developing an action plan as well as evaluating performance on an annual basis. Figure courtesy of Des-Case Corp.

By conducting this type of audit, companies can immediately identify where their weaknesses lie and develop an action plan to close the gap. The key is experience. It can take a lot of wasted time and effort unless you know exactly what you should work on and remain focused on the end goal.

TLT: How do you think lubrication will evolve over the next decade?

Barnes: With many countries, states and industries introducing either voluntary or mandatory reporting of carbon footprint and other environmental measures, companies are having to think about how lubrication impacts environmental compliance more so than ever before. Recently there have been a number of great articles written as well as online tools published to measure the impact that lubricants have on our environment and greenhouse gas emissions.

From production to usage, as well their ability to help extend equipment life, I think the next decade will see a lot of advancement in monitoring lubricant health for condition-based changes, as well as the more broadscale adoption of technologies such as filtration, reclamation and additive replenishment to help get better value from each and every gallon of oil used.

TLT: How big a role do you think online sensors will play in oil condition monitoring in the future?

Barnes: Sensors have come a long way in the past five to 10 years both in terms of functionality as well as price. Today, you can measure wear debris, particle and moisture contamination and oil health with a host of inline sensors that come at a reasonable price. At present, sensors don’t replace what competent oil analysis labs can provide, simply because some of the wet chemistry tests we do on oils and greases, as well as the instrument-based spectroscopic tests such as atomic emission, don’t readily lend themselves to inline sensors. However, as sensor technology evolves there will no doubt be greater and greater adoption of sensor technologies.

In my opinion, those technologies that, not only provide measurements that try to predict issues but use the information to provide correlation with operational conditions, and if possible automated corrective actions, will thrive and become the basis for the next evolution in lubrication technology. There are already companies out there doing just that—for example, using ultrasonic sensors to detect lubricant film thickness connected to automatic single or multiple point grease applications systems to automatically replenish grease on an as-needed basis.

Similar systems that monitor and proactively address lubricant chemistry (additive content, base oil degradation, etc.), coupled with “smart” filtration systems that address the root causes of fluid degradation

(see Figure 2) through fluid process and reclamation, will play an ever-increasing role, as the push to reduce oil consumption continues.

Figure 2. Example of a smart filtration system that includes an onboard particle counter. Figure courtesy of Des-Case Corp.

Figure 2. Example of a smart filtration system that includes an onboard particle counter. Figure courtesy of Des-Case Corp.

TLT: There’s a lot of talk recently about how artificial intelligence (AI) will change the world in the not-too-distant future. How do you think that will impact lubrication and oil analysis?

Barnes: The is no doubt that AI will change our everyday lives in the years to come. But in oil analysis, we have been doing something similar for decades! Every oil analysis lab of size deploys a computer- based expert system to help analyze and interpret results. For example, good labs will use statistical modeling based on asset type, make, model, fuel type, etc. to derive normal versus abnormal wear rates. Likewise, using certain triggers to automatically schedule additional testing or flag results has been in use even 28 years ago when I started in this industry.

What has changed is computing power and accessibility. What used to take a network server to compute can now be done on a smartphone. As computers and algorithms become more powerful, the ability to spot obscure trends or correlations can only be enhanced. The key to successful deployment of AI for condition monitoring will be data integrity. If we don’t have good data, then no computer will ever find the answer. AI is not a solution; it’s just another tool that people will learn to harness to improve asset performance and reliability. Once sensors are deployed, in sufficient scale, providing repeatable, accessible data, the use of AI will provide unparalleled insight and provide much better decision-making capabilities long into the future.

You can reach Mark Barnes at mark.barnes@descase.com.