TLT: Tell us about how you got started in the oil analysis industry.

Lantos: Actually, I got started in the oil analysis industry around age six. My parents, Drs. Jutta and Fred Lantos, established Dr. Lantos Laboratory in January 1960. To our record this is the earliest foundation of an independent commercial oil analysis lab. They were lab staff at the Esso refinery in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and had the genius of understanding that the test methods they ran at the lab were useful to diagnose the breakdown of engines. In the 1960s power lines had not been distributed through the city yet, and each industrial plant or big building had a diesel or gasoline engine and a waste incinerator at the rooftop. Buenos Aires’ atmosphere was actually not so buenos those days. So, Drs. Lantos made a monthly round through the important industrial plants in Buenos Aires, drawing samples and handing reports to the mechanics. Tribology wasn’t even a term back then, and reliability was a concept far less academized. However, banks and corporations needed to keep their lights on.

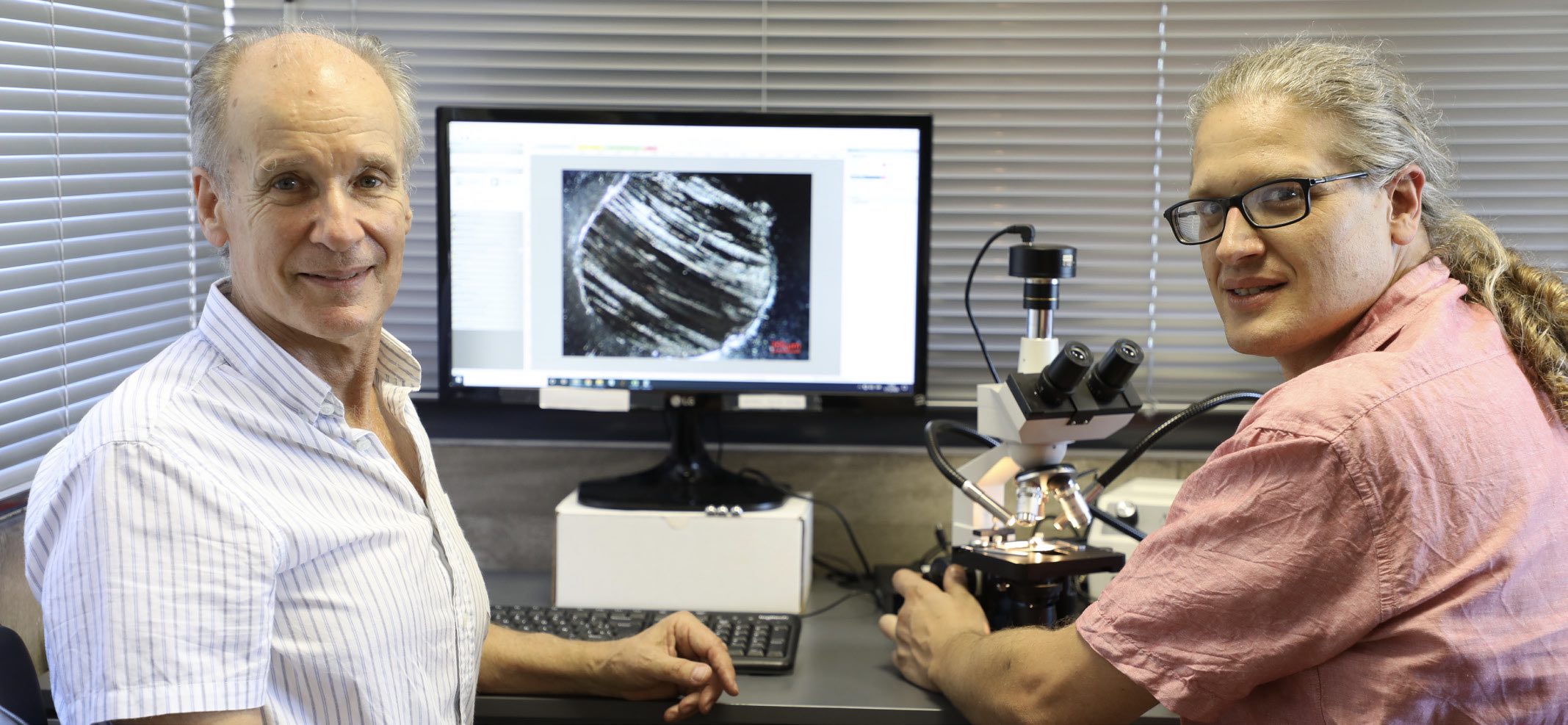

Esteban Lantos (left) and his son Andy Lantos working in the lab.

Esteban Lantos (left) and his son Andy Lantos working in the lab.

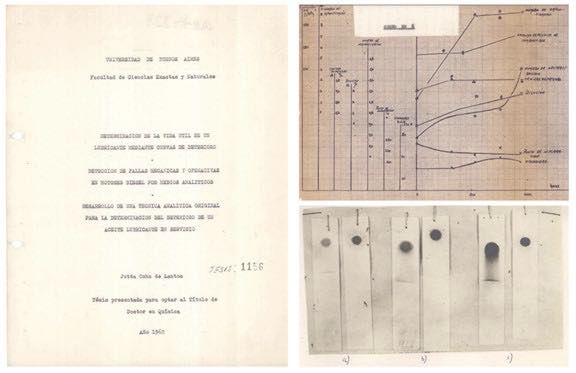

I remember sitting on my father’s lap in our garage running Saybolt viscosities (ASTM D88). Our scope covered crackle, Dean-Stark water (ASTM D95) and flash points (ASTM D92). The standard numbers give an idea of the evolution of the industry in the day and how much can be done with the basics. Around age 10, I was promoted to supervisor of the blotter tests. My mother, Dr. Jutta Lantos, developed the “Lantos” blotter test in her doctoral thesis, in the need to diagnose those diesel engines

(see Figure 1). Toluene was not known to be toxic for kids back then.

Figure 1. Extracts from Dr. Jutta Lantos’ doctoral thesis. The Lantos blotter test method combines the merit of dispersancy of the classical blotter test with the information provided by pentanes and toluene insolubles. Title: Determination of Remaining Useful life of Lubricants Through Deterioration Curves, Detection of Mechanical and Operational Faults in Diesel Engines Through Analytical Methods, Development of a Novel Analytical Method for the Condition Monitoring of In-Service Lubricants. University of Buenos Aires, 1962.

Figure 1. Extracts from Dr. Jutta Lantos’ doctoral thesis. The Lantos blotter test method combines the merit of dispersancy of the classical blotter test with the information provided by pentanes and toluene insolubles. Title: Determination of Remaining Useful life of Lubricants Through Deterioration Curves, Detection of Mechanical and Operational Faults in Diesel Engines Through Analytical Methods, Development of a Novel Analytical Method for the Condition Monitoring of In-Service Lubricants. University of Buenos Aires, 1962.

TLT: How did your involvement in oil analysis change over the years?

Lantos: Lab life and family life have inevitably been intertwined my whole life. Tribology has been the science running down our family and has given me many of the friendships I most cherish. I can recognize three main phases in the development of our lab, which coincide with my youth, middle age and maturity and also are intertwined with the three generations running the lab.

My youth was dedicated to studying the science of tribology, working as an analyst and keeping the lab busy. I became a chemical engineer from the University of Buenos Aires and had the opportunity to attend the tribology seminar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) taught by Ernest Rabinowicz and Nam P. Suh. We had frequent correspondence with Vernon Wescott sharing methods and procedures

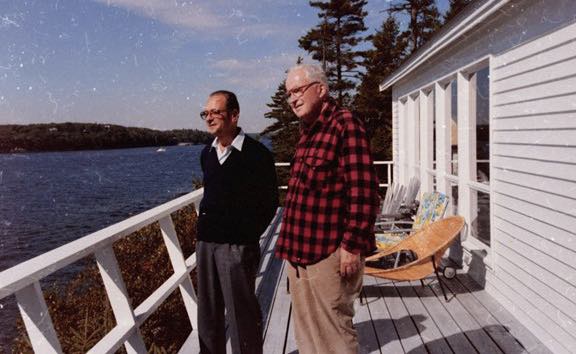

(see Figure 2). My parents traveled every now and then to the U.S. to meet Wescott (Institute Guilfoyle) and Ed Forgeron (Analysts, today Bureau Veritas). It was a pretty small community of pioneers then. I had the opportunity to visit Wescott Lab in 1988 and make friends with an enthusiastic tribologist, a young Ray Daley.

Figure 2. Drs. Vernon Wescott and Fred Lantos, Maine 1975, probably discussing ferrography or blotter tests.

Figure 2. Drs. Vernon Wescott and Fred Lantos, Maine 1975, probably discussing ferrography or blotter tests.

During the 1980s to 1990s I progressively grew in the lab’s leadership, and my interest was to give more service and give a service of excellence—talking to customers, being partners with them and caring to know about their problems, and also feeding with a different perspective to help them think about a solution. To achieve this, we needed to broaden our scope and have a quality assurance (QA) program. Guillermo Rouaux and Alberto Farina were the lab pillars who made it possible. The lab grew to cater for full scope OEM standards for lubes, fuels and transformer oils. We became the trusted partner of our leading industries. Our staff grew from five to 15 in this period.

On the QA side we were early adopters of the “good laboratory practices.” My father was a keen analytical chemist and brought this methodology very early. We adopted ISO 25 around 1995 and accredited ISO 17025 in 2005.

The complement to this growth was my interest in being part of the international condition monitoring community. In 1998 I attended the International Conference on Condition Monitoring in Swansea, Wales, where I met my longtime friend Jim Fitch. That year in October I assisted with the first Noria conference, and we became a Noria partner for Argentina and Uruguay. The community within the Noria international partners and scientists—Jesus Terradillos, David Wooton, Southwest Research Institute’s Janet Barker and Mervin Jones—and our yearly international get-together have given me many good friends and were so nourishing in improving our lab.

In 2015 we were invited to become members of WearCheck International, which coincides with Andy, our middle son, joining the lab full time. This is the start of my third phase in oil analysis.

Andy started participating in the lab pretty young, too—summer jobs burning samples in the rotrode, attending the Noria courses and making pocket money on and off. He studied chemistry as an undergraduate. During his time at university, Terradillos invited him for a summer job at Tekniker, and he came back absolutely amazed with having experienced a worldclass high-throughput lab.

Ten years later, with a doctorate degree, Andy is ready to make it happen for us. He very quickly pushed his way into the core of the lab, not without noise. Together, with the new generation of leadership, we set on the quest to achieve the establishment of a high-throughput WearCheck Lab in Argentina.

Andy dove in and led our lab to a modern, automated data-oriented lab. Our leadership became more diverse, and we built a team packed with interesting talents specializing in so many different areas, from R&D to high-production, QA to marketing and information technology (IT) to customer service—all integrated in a common vision.

To sum up, we believe that generation to generation, still a family-run business, we have the obligation to keep the core values while creating a revolution for the next 20 years.

Esteban Lantos looking through a microscope.

Esteban Lantos looking through a microscope.

Working in the laboratory.

TLT: How do you perceive the differences in doing oil analysis in Argentina versus your colleagues in other countries?

Lantos: This is a conversation that has been around for 60 years, too.

Sample volume, “black samples,” is very different here. Another difference is Andy’s impressions between Tekniker and us 15 years ago and where we are today.

On the other hand, our development for 63 years is not independent of what our industry was expecting from us. We are confident to have fulfilled the needs of our industry and to keep on in this path.

TLT: Along those same lines, what are the challenges and what are the benefits?

Lantos: The challenges are mostly related to the instability and the cyclic crises in the developing countries. It is difficult to project your capital expenditure when it is so uncertain what your return on investment will be. Running business in a +100% year inflation economy is something difficult to explain to folks from developed countries.

The benefits are that being an independent organization, we still have certain liberties to make decisions.

TLT: Can you talk about your transition into production or high-volume oil analysis and how it compares to your research-based business?

Lantos: At the time Andy joined the lab with his new vision, the high-volume oil analysis was a “complement” to classic in-depth tribological analysis. Now, eight years later, high-volume oil analysis accounts for 60% of samples received. While developing high-throughput instruments, we keep a strong line of research-based projects with state-of-the-art instruments and inventive analytical methods.

TLT: Additionally on that topic, would you describe it as a transition or has it been a natural evolution, or something else?

Lantos: I would call this process a synergistic mixture of the three. One line of business calls for the other depending on asset criticality or special failure case.

TLT: How do you see the oil condition monitoring business evolving in the future?

Lantos: The world is spinning faster year after year—electrification, artificial intelligence and robotics. The future looks super exciting, and the industry needs knowledgeable and dedicated consultants. However fast, I consider that our core values and delivering the extra mile will keep on dictating the future in the oil condition monitoring business.

You can reach Esteban Lantos at elantos@lantos.com.ar.