U.S. passenger car engine oil specifications

Don Smolenski, Contributing Editor | TLT Machinery February 2022

An (extremely) abbreviated history on how these have come a long way.

The typical vehicle owner has little appreciation for the great number of step changes in passenger car engine oil performance that occurred over the last seven decades. It would be easy to write volumes on details of the processes used to drive new specifications as well as the specifications themselves. Instead, I have attempted to provide a “Reader’s Digest” condensed version.

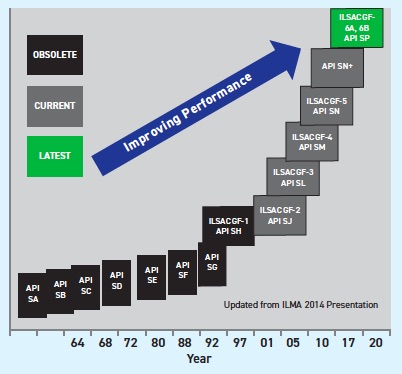

Figure 1 chronicles passenger car (and light-truck) gasoline engine oil specifications over seven decades (the year shown for each category is approximate). In the interest of brevity, I’ll cover American Petroleum Institute (API) and parallel International Lubricant Standardization and Approval Committee (renamed International Lubricant Specification Advisory Committee, ILSAC in either case) specifications.

Figure 1. Passenger car (and light-truck) gasoline engine oil specifications over time. Figure updated from ILMA 2014 presentation.

Figure 1. Passenger car (and light-truck) gasoline engine oil specifications over time. Figure updated from ILMA 2014 presentation.

In the early 1960s and prior, there really were no broadly accepted U.S. engine oil specifications. The industry, through the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and API, drove regular improvements in API categories from SA through SG. In the early 1990s, automakers, frustrated with the time and effort it took to develop new categories, developed their own ILSAC categories, starting with ILSAC GF-1, which ran parallel to API SH. The two systems continue, in parallel, to the now current categories of API SP and ILSAC GF-6A and GF-6B. The two systems’ requirements were substantially similar with, generally, only a few, although not inconsequential, differences. As the categories evolved, they generally covered viscosity requirements (defined by SAE J300), bench test requirements and very rigorous and, generally, expensive engine test requirements. The engine tests were usually run in production engines, so they had unquestioned relevance but required updating periodically as the engines went out of production. Sometimes this necessitated—or at least hastened—the need for a new category.

Improvements occurred with each new category. Engine oils evolved from non-additive base oils to oils formulated to provide:

•

better low-temperature pumping and cranking,

•

better aged oil low-temperature properties,

•

better protection against sludge and varnish,

•

better rust protection,

•

better oxidative stability,

•

better shear stability,

•

better control of high-temperature deposits,

•

better bearing corrosion protection,

•

better valve train wear protection,

•

chain wear protection,

•

less tendency toward low-speed preignition,

•

better fuel economy and fuel economy retention,

•

less tendency toward foaming/aeration,

•

lower volatility for lower oil consumption,

•

better filterability and water tolerance,

•

compatibility with elastomers,

•

85 fuel emulsion retention,

•

lower viscosity grades for better fuel economy and

•

lower phosphorus content and better retention for reduced effects on emissions controls.

In addition, backward compatibility (i.e., new category oils could be used in place of older category oils) was generally achieved. We have come a long way!

FOR FURTHER READING

1.

Smolenski, D. J. (2014), “Challenges of meeting and understanding ever increasing engine oil and transmission fluid specifications,” ILMA 2014 Annual Meeting.

2.

Available

here.

3.

API 1509, American Petroleum Institute, most current version available.

Don Smolenski is president of his own consultancy, Strategic Management of Oil, LLC, in St. Clair Shores, Mich. You can reach him at donald.smolenski@gmail.com.