Progress is moving

Evan Zabawski | TLT From the Editor April 2013

Marking 100 years of efficiency.

From that initial trial, the way automobiles were manufactured would forever be changed.

STLE’S 68TH ANNUAL MEETING & EXHIBITION takes place next month in Detroit. When I think of Detroit, I think of The Big Three— Ford, General Motors and Chrysler, the only three domestic automobile manufacturers to survive the Great Depression and to continue building cars today. Many others have come and gone, or have disappeared through acquisitions, but The Big Three are all still going and are all headquartered in Detroit.

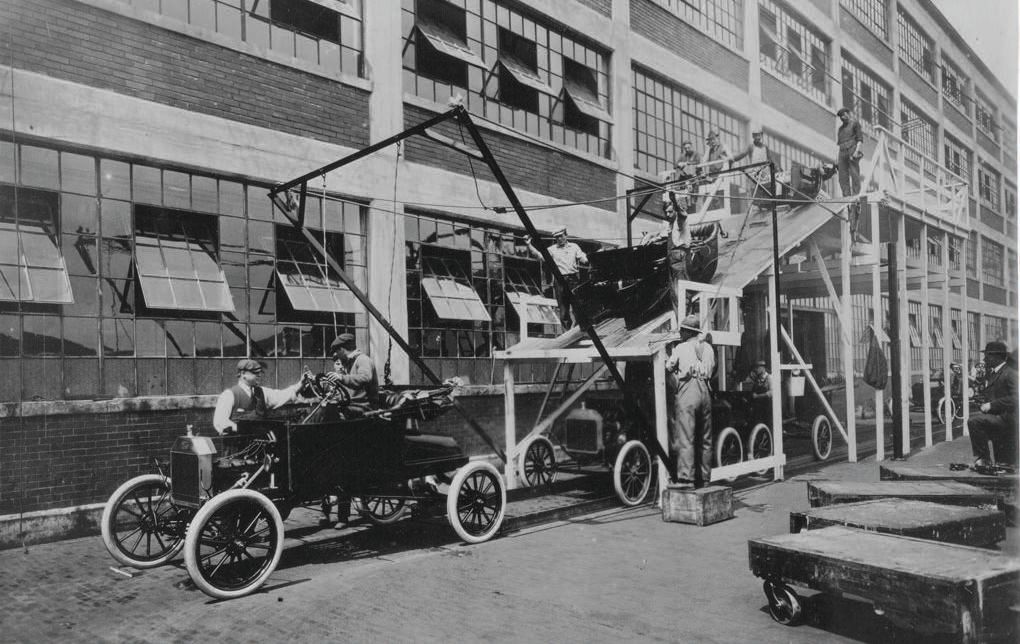

The Ford Motor Co., the oldest of the three, is celebrating an important anniversary this month. The first trial of the moving assembly line took place in Highland Park, Mich., on April 1, 1913. This milestone ushered in a new age of productivity, quality and affordability to the automobile market.

Assembly lines were already in use in the manufacture of automobiles. In 1901 Ransom Olds patented an assembly line concept and used it that same year to build the first mass-produced automobile, the Oldsmobile Curved Dash. Charles Sorenson, a major contributor to Ford’s moving assembly line, said it best, “Henry Ford is generally regarded as the father of mass production. He was not. He was the sponsor of it.”

Another contributor was Walter Flanders. During his 20-month tenure at Ford, he reorganized machine tool placement to coincide with an orderly sequence of operations. After Flanders’ departure in 1908, Sorenson was put in charge of the Piquette plant. In 1910 Sorenson theorized that the cheapest and most efficient way to build an automobile was to have it move in a straight line from one end of the factory to the other. He tested his theory by towing a chassis with a rope over his shoulders through the Piquette plant while others added parts!

In 1912 Henry Ford hired Clarence Avery to be Sorenson’s assistant at the Highland Park plant. Avery trained by working at every phase of production over the next eight months, and over time he became Ford’s time-study expert. Up to this point, Sorenson had spent nearly seven years developing ideas with others on how to modernize and improve the assembly line, and now they had a model that was ready to be tested.

The trial would not be full-scale. It was simply the assembly of a magneto for a flywheel motor. The process originally took 20 minutes, but splitting the process among 29 employees who each performed a singular task reduced the time to 13 minutes. After many months, the height of the line was raised and a moving conveyor was added, which reduced the time to eight minutes and eventually five minutes. This four-fold increase was merely a hint of what was to come.

Until then, a Ford Model T took 728 minutes to fully assemble, but after full-scale application to the whole process it was first reduced to 350 minutes and eventually 93 minutes. This eight-fold increase transposed into a fully assembled Model T rolling off the assembly line every three minutes. It could actually have been faster, but the bottleneck was caused by waiting for the paint to dry. One color dried faster than the rest due to its high bitumen content—Japan Black, which led the company to drop all other choices and invoke one of Henry Ford’s most famous quotes: “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.”

The gains in efficiency reduced the labor requirement and subsequently decreased the cost. In 1908, when Flanders was making his first tweaks, a Model T cost $825. It rose to $850 in 1909, but then dropped to $550 in 1913 and $440 in 1915, with the majority of Sorenson’s major adjustments in place.

From that initial trial, the way automobiles were manufactured would forever be changed. The moving assembly line is perhaps Ford’s greatest contribution to automotive manufacturing.

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is reliability specialist in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at evan.zabawski@gmail.com

Evan Zabawski, CLS, is reliability specialist in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. You can reach him at evan.zabawski@gmail.com.