Introducing new products

Peter A. Oglevie | TLT Shop Floor February 2010

Pick the right time for your test and include all secondary operations.

The time to introduce a lubricant is not during a production run.

www.canstockphoto.com

My personal war with Old Man Winter rages on. He sends a blizzard, I get the snow blower (tool). He sends a dusting of snow, I get the snow shovel (tool). He sends a freezing rain, I get out the salt (chemistry). For every punch he throws, it seems I have a counterpunch. The problem is the time it takes to get back to normal after each punch.

The shop floor is a lot like the weather. You never know when it will send its next nasty little surprise, and you do not know how much time it will take to overcome the difficulty. That is why shop floors spend so much time streamlining their manufacturing processes.

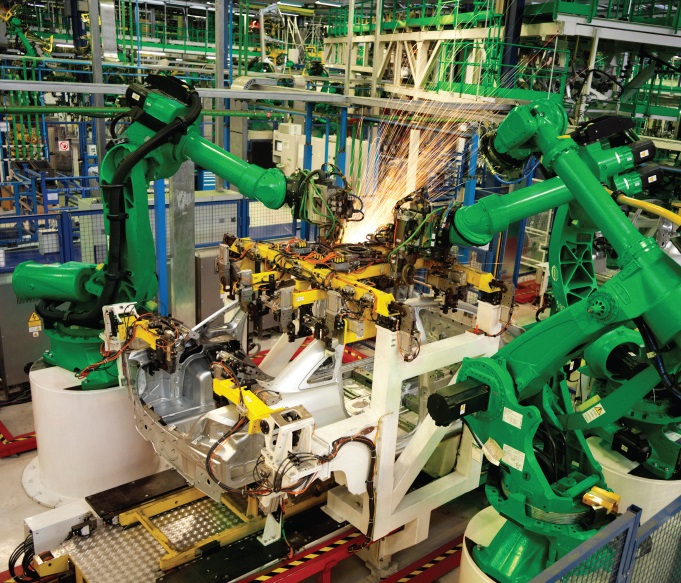

Let’s look at two areas that cause the majority of problems with metalworking fluids, the lubricant where we generally have the greatest need for new products. The first is tool life. The second is part finish.

Tool life and making the part are the most important. If you cannot make the part, the rest of the process is irrelevant. The shop floor is much like the weather. You get new jobs to make, and you have the same tools (lubricants) to make them. This is kind of like fighting a 15-inch snowstorm with a snow shovel. The shovel works, but a snow blower is better.

Consider an order of 100,000 parts. If the scheduler has set aside 40 hours of time on a machine that produces 50 parts per minute, you have 6 ½ hours for the setup and any problems that come up during the run. If setting up the machine takes 20 minutes, you have six hours for problems. If you take three hours to pull the tool from the machine for tool room work, you have three hours left. Pull the tool one more time, take 20 minutes to reset the machine, and you have only two hours and 40 minutes to finish a three-hour job. There is not enough time.

This is when the panic call comes in to you, the lubricant supplier. You will hear things like, “Your oil is no good.” In reality, the difficulty could be a tool, material or machine problem, but the pressure will be to get the machine running and keep it running. In response, you introduce a new lubricant one or two steps up the matrix in terms of performance and finish the job.

Everyone breathes a sigh of relief because the job is out of the machine. The next day you get a call from the finishing department. They are under pressure to get the parts out the door, and they cannot get the lubricant off. At this point, the new product that made you a hero the day before will have you in deep doo-doo.

We should have worked on the chemistry for the process in advance. The lubricants we put on have to come off. With snow, even though I remove the majority of the snow with tools, some snow and ice remain bonded to the sidewalk. For this portion of the job, I have to use chemistry.

The time to introduce a lubricant is not during a production run unless extra machine time has been set aside to test the product. The test also should examine how the lubricant performs with secondary operations like welding, brazing, plating or painting.

I learned the hard way that if you cannot do it right, don’t do it. If that saves you from a huge problem, this column will have been worth writing.

Pete Oglevie is president of International Production Technologies in Port Washington, Wis. You can reach him at poglevie@wi.rr.com

Pete Oglevie is president of International Production Technologies in Port Washington, Wis. You can reach him at poglevie@wi.rr.com.