Turbines: What goes around comes around

Dr. Robert M. Gresham, Contributing Editor | TLT Lubrication Fundamentals December 2009

There are three main types of turbomachinery, and each has its own set of lubrication requirements.

KEY CONCEPTS

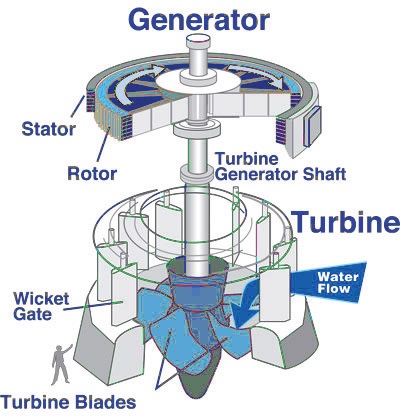

• Hydro-turbines are driven by water and connect to an electricity generator or more properly turbo-alternator to produce electricity.

• Industrial steam turbines have multiple uses such as driving compressors, turbo-alternators, blowers and pumps.

• Gas turbines are a good application for synthetic lubricants such as polyalphaolefins and ester-based oils.

I make no claim to being an expert in turbomachinery, but these gadgets have always intrigued me as a class of machinery. At STLE’s Annual Meeting & Exhibition, most of the education courses and practical papers tend to gloss over lubrication of turbomachinery.

So here goes.

In the world of turbines, there are three main types: hydro, steam and gas. Well, I guess you should also include wind turbines, but they are quite a bit different than the above three. While I suppose you could call wind turbines a special case of a gas (air) turbine, to me they are a big wind-driven propeller hooked up to a gearbox that is, in turn, hooked up to a generator or alternator.

HYDRO-TURBINES

These machines are driven by water and connected to an electricity generator or, more properly, a turbo-alternator to produce electricity. Hydro-turbines are on the low end in terms of application requirements but still significant. Thus, the lubricating oil sees temperatures in the oil sump on the order of 40 C-60 C with peak temperatures in the circulation system to maybe 70 C-95 C. Speeds are also moderate at around 50-600 rpm.

The oil also must lubricate guide vanes and control system components. The main lubrication issues for these kinds of turbines are water contamination and service life. Thus, mineral oil-based R&O oils that have good water demulsibility are needed. The long service life is desirable to reduce maintenance costs and downtime. These are important due to the physical location of these turbines and the need for uninterrupted electrical power output.

STEAM TURBINES

Industrial steam turbines have multiple uses, usually to drive compressors, turbo-alternators, blowers, pumps and the like. In compressor applications, steam turbines and the compressor itself are similar in that they are both turbomachines. As such, they can behave similarly in terms of speed vs. output. Thus, steam turbines are excellent for variable-speed turbo-compressors.

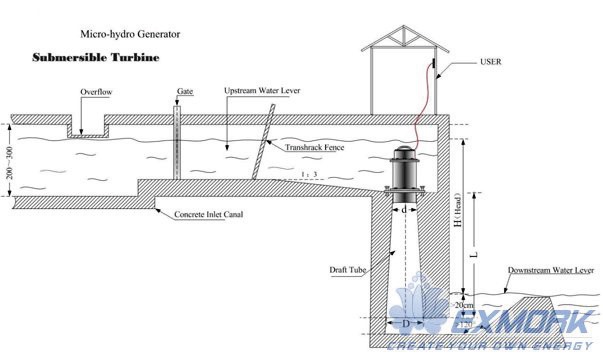

Figure 1. Schematic of a hydro-turbine installation.

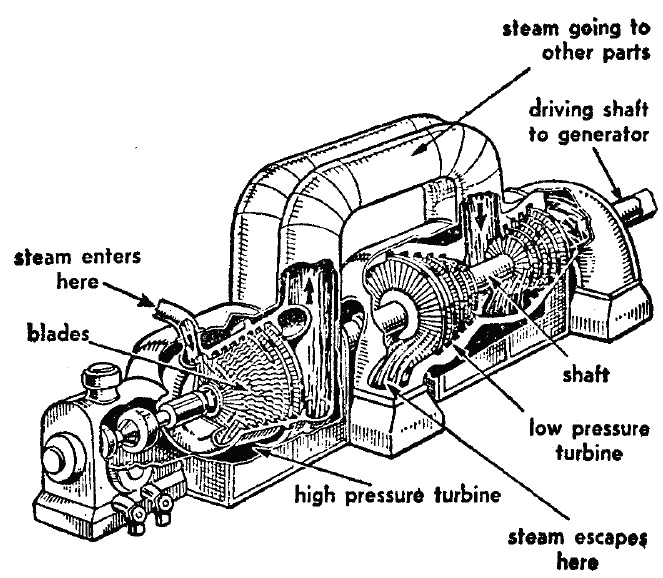

Figure 2. Schematic of a steam turbine.

Figure 3. Schematic of a hydro-turbine.

Figure 4. A steam turbine installation.

Steam turbines can take on many different configurations, an analysis of which goes beyond the scope of this article. However, all multistage steam turbines require cool, clean oil supplied to their journal bearings.

This oil is supplied from several types of systems, but the key is that the oil must be delivered at the right flow rate, pressure and temperature. Often the driven equipment, such as the compressor, is also lubricated with the same oil, again at the right level of cleanliness, flow, pressure and temperature. Furthermore, additional equipment also might be lubricated by this same system such as various control valves.

In general terms, steam turbines can operate up to speeds of 3,000 rpm, oil sumps around 40 C-70 C with peak or hot spot temperatures as high as 150 C. Clearly, aside from particulate contamination, which is always a problem, steam turbines are subject to the effects of water and steam. Typically turbine oils for steam turbines must be primarily resistant to rust and oxidation, the so-called R&O oils. Additionally, turbine oils may contain antiwear and EP additives. Further, they should exhibit good demulsibility of water and be low foaming.

Interestingly, when one thinks about the highly formulated automotive oils (10%-20% additives), turbine oils by contrast are typically formulated with not much more than 1% additives. Therefore, the base oils are important. They can vary from Groups II, II, II+ or IV. The higher refined oils tend to have more inherent oxidation stability but, especially in the old days, they also tended to exhibit more varnish formation, likely because less refined oils tend to solublize varnish rather than letting it form deposits.

More modern formulations along with effective filtration generally manage excessive varnish formation, or at least they should. Such oils typically have a viscosity index (VI) in the range of 95-100 so that the viscosity doesn’t vary too much from startup to peak temperatures.

GAS TURBINES

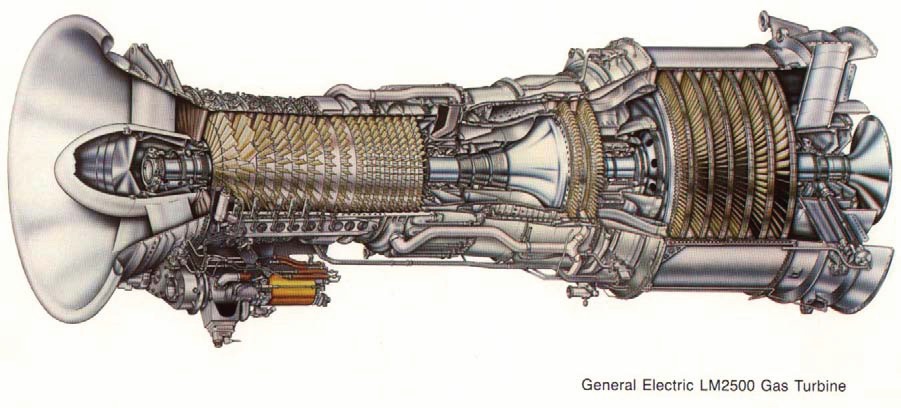

Industrial gas turbines, which are basically land-based jet engines (windmills notwithstanding), have some similarities to steam turbines except that steam is replaced with hot combustion gases. Thus, water contamination is not so much a problem with gas turbines. However, sump temperatures can range between 50 C-100 C with hot spot peaks up to 280 C. Speeds also are higher on the order of 3-7,000 rpm. Therefore, the performance requirements of the lubricating oil are necessarily higher, while lubricating oils based on hydrotreated basestocks are used for the less stringent applications.

Clearly, gas turbines are a good application for synthetic lubricants such as polyalphaolefins and ester-based oils. Many of the larger, higher-performing industrial gas turbines (like the one shown in Figure 5) often use an aircraft engine core and require similar lubricants. For more advanced aircraft jet engines, which really are just higher-performing gas turbines, we have to kick it up a notch.

Figure 5. General Electric LM2500 Gas Turbine

These turbines use primarily ester-based lubricants for their wide-temperature range capabilities such as those described by military specifications MIL-L-7808 and MILL-23699. For even higher-temperature resistance with operating temperatures as high as 300 C, polyphenylether lubricants, as described in MIL-L-87100, could be used. But these are not for the financially faint of heart, and the polyphenylethers have poor low-temperature performance, which is not so critical for an industrial gas turbine but can be a showstopper for an airplane.

Clearly, turbomachinery, like the applications described above, affect our everyday lives in many ways. Keeping them going around allows us to go around.

Bob Gresham is STLE’s director of professional development. You can reach him at rgresham@stle.org.